By Brian Britton French

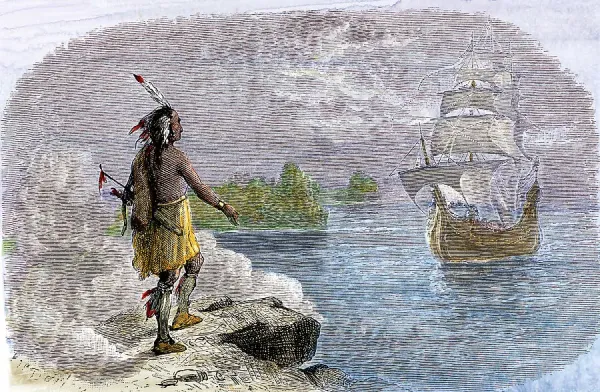

The technological and political gap that existed in 1620 between Western European societies and the Native peoples of eastern North America was not primarily caused by any inherent intellectual or cultural inferiority.

It is far better explained by two interlocking geographic realities: (1) an extreme abundance of land relative to population, and (2) the long-term geographic isolation of the Americas from the high-density, high-interaction core of European / Asian civilizations. These two factors powerfully constrained incentives and opportunities for the kind of cumulative technological and societal advancement that occurred in Europe and Asia vs. North America.

Land Abundance and the “Frontier Brake” on Complexity

In 1500, the entire land area of what is now the United States and Canada (roughly 2 billion acres) supported perhaps 4–7 million people north of the Rio Grande. That is an average density of roughly 1 person per 300–500 acres. In contrast, late-medieval England had ~1 person per 20–25 acres, France ~1 per 15–20 acres, and the most fertile parts of China and northern India reached 1 person per 3–6 acres.

What does extreme land abundance do to a society?

- Agriculture stays extensive, not intensive. With new fertile land always available by moving a few dozen miles (or simply letting fields lie fallow for 10–20 years), there is almost no pressure to invent the plow, the moldboard, three-field rotation, or heavy manuring. Most eastern North American societies practiced slash-and-burn or flood farming with digging sticks.

- Labor-saving devices are not rewarded. Why invent the wheel, the draft horse harness, or water mills when human labor is relatively plentiful and land is essentially free? In Europe, acute land scarcity made every marginal increase in yield per acre (technology) worth an enormous investment.

- Geographically dispersed and mobile inhabitants are hard to unite. When dissatisfied native American farmers can simply walk away into the next river valley and start a new village, political leaders have a very hard time extracting the surplus needed for standing armies, stone cities, or bureaucratic hierarchies. The two largest pre-contact polities north of Mexico—Cahokia (peaked ~1100 CE) and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy—collapsed or remained deliberately decentralized for exactly this reason. Cahokia’s population fell from ~20,000–40,000 to near zero within a century once the local maize boom ended and people voted with their feet.

- Warfare stays small-scale and ritualized. With so much empty or lightly held land, the objective of war was usually captives, prestige, or revenge—not permanent conquest of territory. This further reduces the selective pressure for military revolution (bronze cannons, disciplined infantry, taxation systems to support them, etc.).

Geographic Isolation from Eurasian “The Luckiest Continent”

From roughly 12,000 BCE until 1492, Native Americas were essentially cut off from the Old World disease pools and technology distribution networks. Eurasia, by contrast, is a single vast east-west band at similar latitudes, allowing crops, animals, ideas, and technologies to spread rapidly from China to Spain. The wheel, bronze, iron, the horse, the plow, alphabetic writing, and gunpowder all spread (or re-spread) across thousands of miles in a relatively short period of time.

The Americas are north-south oriented, with drastic latitude/climate shifts every few hundred miles, blocking easy diffusion of crops and animals. The result:

- No large domesticable animals except the llama/alpaca (Andean only) → no draft power, no cavalry, no epidemic diseases to create immunity.

- Metallurgy remained at copper/gold decorative level in most areas; iron working never appeared north of central Mexico.

- Wheeled vehicles were invented (as toys) in Mesoamerica but never used practically because there were no draft animals.

- Writing systems were limited to Maya glyphs and a handful of others; no alphabetic literacy that could spread easily.

While the Old World had 5,000+ years of constant warfare, trade, and competition among dozens of states in a connected macro-region, the Americas had pockets of high civilization (Olmec → Maya → Aztec; Chavín → Inca, etc.) that rose and collapsed with almost no cross-fertilization to the vast area north of the Rio Grande.

The Combined Competitive Disadvantages of Native Americans by 1620

By the time the Mayflower arrived, Europe had been forced by land scarcity and constant interstate competition into:

- ocean-going ships

- iron weapons and cannons

- the joint-stock company

- global trade, currency and double-entry bookkeeping

- the printing press

- standing armies supported by sophisticated taxation

Native societies in the Northeast had abundant game, fish, and fertile soil after the 1616–19 epidemic, and almost no population pressure or external existential threat that would force parallel revolutions. They were not “behind” in any moral sense; they were perfectly adapted to a continent where land was limitless and the rest of the world’s technological arms race was unknown and unreachable.

In short: the same geographic conditions that made North America look “empty” and “available” to the Pilgrims in 1620 are precisely the conditions that kept Native societies small-scale, low-density, and technologically underdeveloped from the crowded, hyper-competitive European / Asian core for the previous 15,000 years.

Abundance of land and isolation from the Old World innovation cluster explain the gap far better than any appeal to innate ability or cultural superiority.

At the moment the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, the Native inhabitants of the Atlantic coast lived in the following technological and organizational reality:

Stone Age toolkit: No metal tools or metal weapons of any kind (bronze, iron, or steel). All cutting implements were stone, shell, bone, or wood.

No wheel: The wheel was completely unknown for transport or mechanical advantage — no carts, wagons, pulleys, or wheeled devices of any kind.

No beasts of burden: Only dogs were domesticated for carrying or pulling; no horses, oxen, or other large draft animals existed north of Mexico.

Water transport limited to canoes: Largest vessels were birchbark or dugout canoes (20–50 ft); none had keels, multiple masts, or true ocean-going capability — they were canoes, not ships.

Population already decimated: The 1616–1619 plague had killed 50–90% of coastal Natives in New England before the Mayflower even sailed; many villages the English found were ghost towns. The same diseases equally ravaged Europe for hundreds of years.

Political organization: Regional chiefdoms (e.g., Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom ruling ~30 tribes and 15,000 people) and tribal alliances, but no continent-wide unity and frequent inter-tribal warfare.

No writing system: Knowledge was entirely oral; records kept via wampum or mnemonic devices.

Largest settlements in 1620: A few thousand people at most; the great pre-contact urban centers farther inland had collapsed centuries earlier.

This technological and demographic gap was decisive. Throughout recorded human history — from the Sumerians absorbing weaker tribes, to the Han Chinese expanding southward, to the Bantu migrations across Africa, to the Romans, Arabs, Mongols, and later European powers — more prosperous, technologically advanced, and demographically robust civilizations have always displaced, absorbed, or overpowered less advanced neighbors when they came into sustained contact. This is a near-universal pattern of history and was not unique to North America.

In the specific case of European settlement of the Eastern Seaboard, the process was not primarily driven by malice or a premeditated campaign of genocide. The English (and later other Europeans) came as settlers (i.e., families) seeking land, and religious independence not as conquering armies seeking to exterminate. The overwhelming majority of Native population loss came from unintentional disease, not deliberate killing. Once the demographic collapse occurred and English numbers grew through immigration, the outcome — displacement and loss of Native sovereignty — was effectively inevitable, just as it had been inevitable when earlier advanced civilizations met weaker ones across the planet for the previous 5,000 years.

Fact-based comparative analysis of Native societies in the Mayflower region versus 17th-century Europeans

Architecture

| Europeans (circa 1620) | Native Peoples of New England (1620) |

|---|---|

| Stone and brick buildings, multi-story houses | Wood-frame wetus and longhouses, typically single-room structures |

| Cathedrals, castles, reinforced masonry | No stone or masonry large-scale architecture |

| Load-bearing walls, arches, chimneys, glass windows | Bark/reed insulation, smoke-ventilation holes, no glass or chimney |

| Cities permanently anchored | Seasonal settlement movement common |

Result: Europe was far more advanced in construction engineering, material science, and architectural scale.

Art and Material Culture

| Europeans | Native New England |

|---|---|

| Oil painting, sculpture, advanced metallurgy | Carving, quillwork, beadwork, wood sculpture |

| Permanent art in stone and canvas | Art practiced mainly on perishable materials |

| Dedicated artistic guilds and patrons | Art integrated into functional objects (clothing, tools) |

Result: Europe produced larger, more durable, and more technically complex art forms.

Writing and Record-Keeping

| Europeans | Native New England |

|---|---|

| Alphabetic written language | No writing system |

| Books, legal contracts, maps | Oral memory and wampum mnemonic systems |

| Literacy among elites and merchants | Literacy absent (no written format to teach) |

Result: Europeans had a literacy-driven culture; New England tribes were non-literate.

Roads and Infrastructure

| Europeans | Native New England |

|---|---|

| Engineered road networks connecting countries | Footpaths connecting settlements |

| Bridges, paved highways | No bridges, paving, or engineered large-scale road networks |

| Draft-animal transport | Human and dog transport only |

Result: Europeans were vastly superior in transportation engineering.

Trade and Economic Scale

| Europeans | Native New England |

|---|---|

| International merchant class | Regional barter networks |

| Market economy using metal coinage | Trade using wampum and goods |

| Currency, credit, investment capital | Trade based on reciprocity and obligation |

| Large cargo ships moving bulk goods | Canoes moving small cargo in rivers/coastline |

Result: Europeans operated a monetary global trade system; New England tribes used localized trade systems.

Printing Press and Information Transmission

| Europeans | Native New England |

|---|---|

| Printing press widespread | No printing technology |

| Book publishing, newspapers emerging | No mass communication mechanism |

| Written scientific, legal, religious texts | Oral tradition only |

Result: Europe had exponential information storage and transmission capability; Native societies did not.

Scale of Cities and Population Density

| Europeans | Native New England |

|---|---|

| Cities in tens or hundreds of thousands (London ~300,000) | Settlements typically a few hundred to a few thousand |

| Permanent urban centers | Semi-mobilized village networks |

| Multi-story dense population | Low-density distributed population |

Result: Europe had true urban civilization; the Northeast was rural and low-density.

Merchant Shipping and Naval Technology

| Europeans | Native New England |

|---|---|

| Deep-keel ocean ships (200–500 tons) | Birchbark or dugout canoes |

| Navigation by map, compass, astrolabe | Coastal navigation via memory and landmarks |

| International transport of cargo | Local/regional transport only |

| Cannons, sails, multi-mast rigs | No metallurgy, no sails, no naval artillery |

Result: The gap here is the most extreme — Europe was operating at a global-maritime scale; New England tribes were at river-and-shore transport scale.

Summary from a Comparative Civilizational Standpoint

| Category | Civilizational Level in 1620 | Winner |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Europe far ahead | Europe |

| Writing | Europe far ahead | Europe |

| Roads | Europe far ahead | Europe |

| Art | Europe more technically developed | Europe |

| Agriculture | Comparable in efficiency; different systems | Tie |

| Trade | Europe far ahead in scale and complexity | Europe |

| Printing | Europe far ahead | Europe |

| Cities | Europe far ahead | Europe |

| Merchant Shipping | Europe overwhelmingly ahead | Europe |

Historical Conclusion

In technology, material culture, infrastructure, communication, and urban scale, Europeans were dramatically more advanced than the Native peoples of New England in 1620.

Native societies were skilled in living efficiently within their environment, but they were not at a comparable developmental stage to 17th-century European civilization.