By Brian Britton French

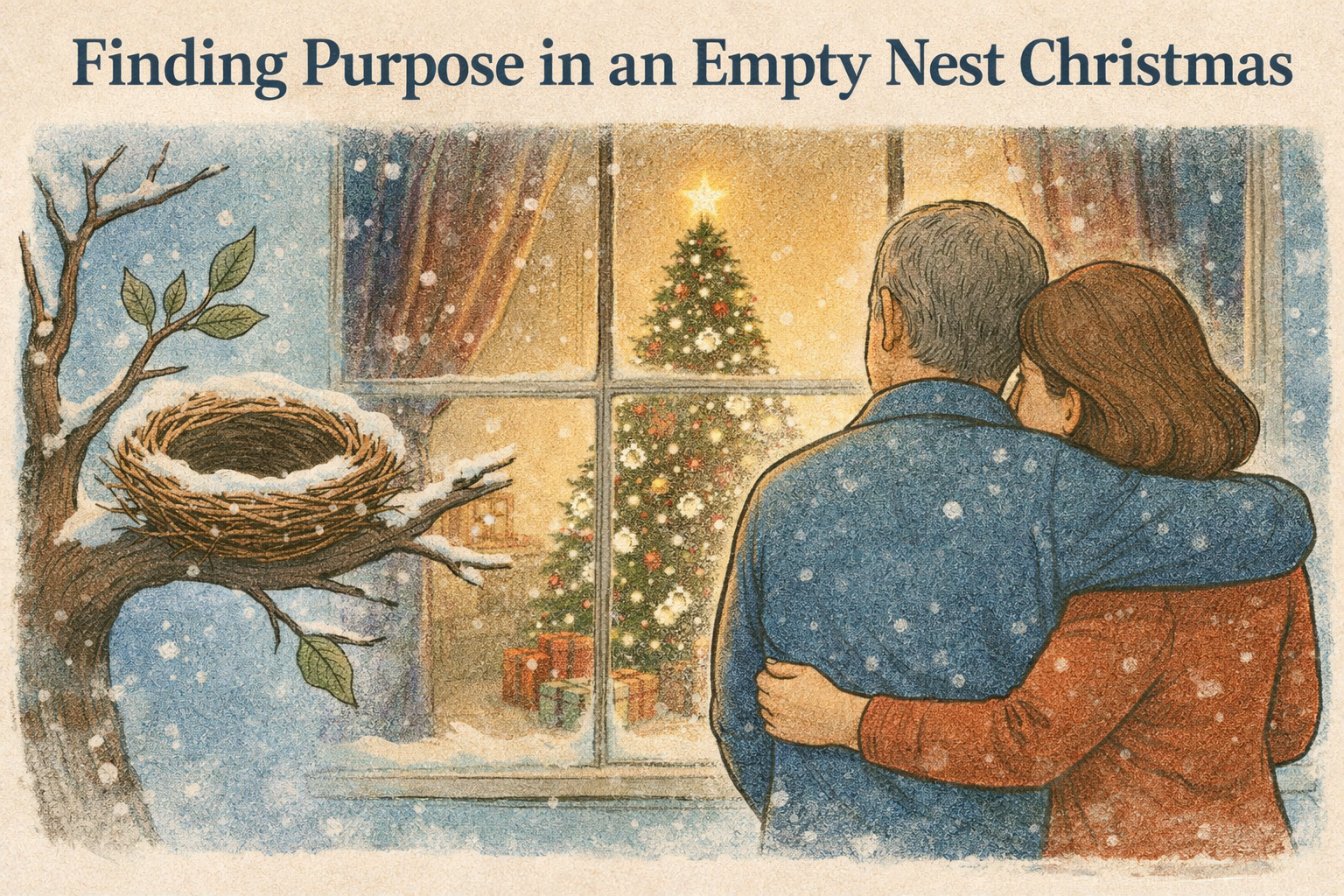

The house is quiet now. Too quiet. The kind of quiet that amplifies memory, that makes you hear phantom footsteps on the stairs and imaginary giggling echoing from rooms that once vibrated with excitement. I walk past the living room where the Christmas tree stands, and I can almost see them—those small bodies in their flannel pajamas, faces pressed against the windowpane, breath fogging the glass as they watched and listened for any sign that reindeer had landed on our roof.

They’re grown now, my children. They have their own lives. And I am happy for them—genuinely, happy. But there’s a hollow place where their need for me used to be, a void shaped like bedtime stories and scraped knees and the thousand small emergencies that made me essential to someone’s world.

Wordsworth knew something about loss and time. In his “Ode: Intimations of Immortality,” he wrote of youth’s vanished glory: “Though nothing can bring back the hour / Of splendor in the grass, of glory in the flower; / We will grieve not, rather find / Strength in what remains behind.”

Those lines have taken on new weight in these quieter years. The splendor has indeed faded from certain seasons of my life, and I have grieved—more than I expected to. But Wordsworth wasn’t counseling resignation. He was pointing toward transformation.

The need to be needed doesn’t disappear when your children grow up. It simply goes looking for new places to land, new ways to matter. And here’s what I’ve discovered: it’s everywhere, if you’re paying attention.

It’s in the face of the man who cuts my lawn every week, who works three jobs and still shows up with a smile when the heat index hits one hundred. It’s in the hands of Emilee at the grocery store, her dignity overwhelms her cerebral palsy in every deliberate movement and kind remark she makes.

These people help me all year long. They make my life work. And most of them, I’ve realized with some shame, are nearly invisible to me—or they were, until I started really seeing them. They don’t expect tips. They don’t expect to be remembered. They show up, do their work, and go home to their own complicated lives, their own bills and worries and dreams deferred.

The prices of everything have climbed, but the wages of the people who serve us—who help us—haven’t kept pace. The checkout clerks and baggers, the lawn workers and delivery drivers they’re falling further behind while we debate economic policy in the abstract.

But we’re not powerless. We can inflate our hearts along with the economy. We can build our own personal stimulus plan. I’m identifying everyone who helps me throughout the year—the people I depend on, and I’m giving them a raise. Twenty percent feels about right, maybe more if I can swing it.

Tipping them and paying them extra isn’t charity. It’s justice, small-scale and personal.

Here’s the return on investment part: it fills that void in my own life, that need to be needed, that purpose-shaped hole left behind when my kids grew up and moved on.

This Christmas, there won’t be small children in PJ’s tearing through Christmas wrapping paper in the living room with glee. But there will be moments of eye contact and recognition, of one human being telling another: you are seen, you are valued, you make a difference in my life and I am grateful.

The splendor in the grass, the glory in the flower—those belong to the past. But there is splendor in the present too, if we choose to create it.

Life is short… give those around you (and yourself) the gift of gratefulness this Christmas.